DeepSpeed-MoE for NLG: Reducing the training cost of language models by 5 times

Autoregressive transformer-based natural language generation (referred to as NLG in the rest of the blog) models can offer convincing solutions to a broad range of language tasks from document summarization, headline generation, question and answering to even generating code in a wide variety of programming languages. Due to the general applicability of these models, improving their quality has been of great interest for both academia and industry alike.

The quality of NLG improves with the increase in model size. However, today we are getting close to the limit of what the current generation of hardware can do. The Megatron-Turing NLG 530B model took 3 months to train on over 2K A100 GPUs on the NVIDIA Selene Supercomputer, consuming over 3 million GPU hours. Another 3 to 5 times of increase in model size would be infeasible within a reasonable timeframe. Given the exorbitant compute resources required to train the state-of-art NLG models, a natural question to ask is: “Is it possible to make non-trivial improvement to model quality without increasing the compute cost?” Or equivalently, “Is it possible to produce model with similar quality using 3 to 5 times less resources?”

Recent works like GShard and Switch Transformers have shown that Mixture of Experts (MoE) model structure reduces large model training cost significantly for transformer-based encoder-decoder models. An MoE model contains a set of sparsely gated experts. During training and inference, only a subset of these experts is activated for each input token. Therefore, the model could scale to billions of parameters without a proportional increase in the computation. Despite showing promising results, the effectiveness of MoE for the much more computation intensive NLG family models remains mostly unknown.

Given the tremendous compute and energy requirements for training NLG family of models, we explore the opportunities that MoE presents to reduce their training cost. We show that MoE can be applied to NLG family of models to significantly improve their model quality with the same training cost. Alternatively, it can achieve 5x reduction in training cost to achieve the same model quality of a dense NLG model. For example, by applying MoE we achieved the model quality of a 6.7B parameter dense NLG model at the cost of training a 1.3B parameter dense model, thanks to the sparse structure of MoE.

Assuming the scaling holds, the results have the potential to completely transform the large model training landscape in terms of cost. For example, a trillion-parameter dense model can be potentially trained at the cost of a 200B parameter (like GPT-3) sized dense model, translating to millions of dollars in training cost reduction and energy savings (Brown et al., 2020, Language models are few-shot learners).

MoE based NLG model architecture

To create an MoE based NLG model we studied the GPT like transformer-based NLG model. To complete training in a reasonable timeframe, the following models are selected: 350M (24 layers, 1024 hidden size, 16 attention heads), 1.3B (24 layers, 2048 hidden size, 16 attention heads), and 6.7B (32 layers, 4096 hidden size, 32 attention heads). We use “350M+MoE-128” to denote a MoE model that uses 350M dense model as the base model and adds 128 experts on every other feedforward layer. That is to say, there are in total 12 MoE layers for both 350M+MoE-128 and 1.3B+MoE-128.

We use a gating function to activate a subset of experts in the MoE layer for each token. Specifically, in our experiments, only the top-1 expert is selected. Therefore, during both training and inference, our MoE model will have the same number of parameters to be activated for each token as their dense part. For example, our 1.3B+MoE-128 will only activate 1.3B parameter per token, and the amount of training computation per token will be similar to a 1.3B dense model.

MoE training infrastructure and dataset

We pre-trained both the dense and MoE version of the above models using DeepSpeed on 128 A100 GPUs. DeepSpeed uses a combination of data parallel and expert parallel training to effectively scale the MoE model training.

We used the same training data as described in the MT-NLG blog. For a fair comparison, we use 300B tokens to train both the dense model and the MoE model.

MoE leads to better quality for NLG models

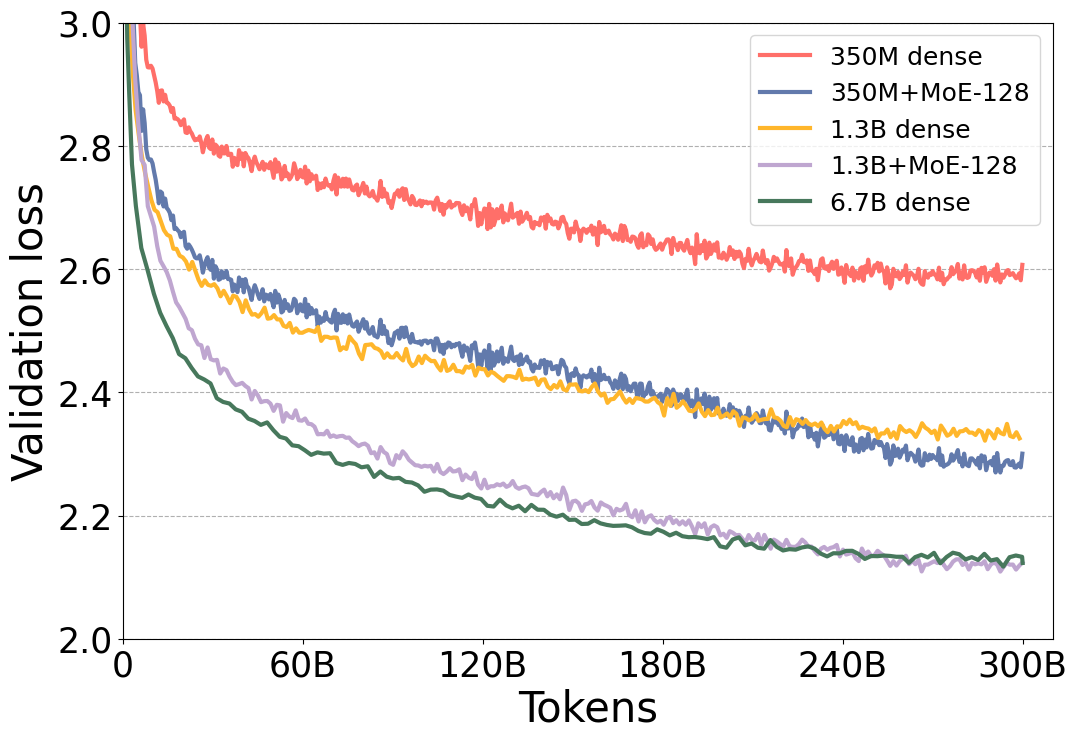

Figure 1 shows that the validation loss for the MoE versions of the model is significantly better than their dense counter parts. Furthermore, notice that the validation loss of the MoE model, 350M+MoE-128, is on par with the validation loss of the 1.3B dense model with 4x larger base. This is also true for 1.3B+MoE-128 in comparison with 6.7B dense model with 5x larger base. Furthermore, the model quality is on par not only for the validation loss but also for a wide variety of 6 ZeRO-shot evaluation tasks as shown in Table 1, demonstrating that these models in fact have very similar model quality.

Figure 1: Token-wise validation loss curves for dense and MoE NLG models with different model sizes.

| Model size | LAMBADA: completion prediction | PIQA: commonsense reasoning | BoolQ: reading comprehension | RACE-h: reading comprehension | TriviaQA: question answering | WebQs: question answering |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Dense NLG: | ||||||

| 350M | 0.5203 | 0.6931 | 0.5364 | 0.3177 | 0.0321 | 0.0157 |

| 1.3B | 0.6365 | 0.7339 | 0.6339 | 0.3560 | 0.1005 | 0.0325 |

| 6.7B | 0.7194 | 0.7671 | 0.6703 | 0.3742 | 0.2347 | 0.0512 |

| MoE NLG: | ||||||

| 350M+MoE-128 (13B) | 0.6270 | 0.7459 | 0.6046 | 0.3560 | 0.1658 | 0.0517 |

| 1.3B+MoE-128 (52B) | 0.6984 | 0.7671 | 0.6492 | 0.3809 | 0.3129 | 0.0719 |

Table 1: ZeRO-shot evaluation results (last six columns) for different dense and MoE NLG models. All ZeRO-shot evaluation results use the accuracy metric.

Same quality with 5x less training cost

As we saw from the results above, adding MoE with 128 experts to the NLG model significantly improves the quality of the NLG model. However, these experts do not change the compute requirements of the model as each token is only processed by a single expert. Therefore, the compute requirements for dense model and its corresponding MoE models with the same base are similar.

More concretely, a 1.3B+MoE-128 model training requires roughly the same amount of compute operations as 1.3B dense, while offering much better model quality. Furthermore, our results show that by applying MoE we can achieve the model quality of a 6.7B parameter dense model at the training cost of 1.3B parameter dense model, resulting in an effective training compute reduction of 5x.

This compute cost reduction can directly be translated into throughput gain, training time and training cost reduction by leveraging the efficient DeepSpeed MoE training system. Table 2 shows the training throughput of the 1.3B+MoE-128 model in comparison to the 6.7B dense model on 128 NVIDIA A100 GPUs.

| Training samples per sec | Throughput gain / Cost Reduction | |

|---|---|---|

| 6.7B dense | 70 | 1x |

| 1.3B+MoE-128 | 372 | 5x |

Table 2: Training throughput (on 128 A100 GPUs) comparing MoE based model vs dense model that can both achieve the same model quality.

MoE for Inference

The training cost reduction of MoE is not free and comes at the expense of increasing the total number of parameters required to achieve the same model quality compared to dense models. The 1.3B+MoE-128 have roughly 8x the number of parameters (52B) compared to the 6.7B dense model. So, does this mean inference will be 8x slower than the dense model, since inference is generally limited by the time taken to read all the model parameters, especially for small batch sizes?

Not quite. Note that in the 1.3B+MoE-128 model, each token is processed by a unique expert per MoE layer, and the total number of parameters used in processing the token is just 1.3B. This can in theory result in even faster inference than the quality-equivalent dense 6.7B model because of 5x less compute and parameter read. In reality though, the number of tokens in a batch during inference is generally larger than 1. Inferencing, a long sequence length or a non-unit batch size may require loading all the experts, increasing the total number of parameters loaded by 8x compared to the quality-equivalent dense model. Therefore, achieving good inference performance with MoE is still challenging even though the parameters used and the computation incurred per token is small compared to the quality-equivalent dense model.

Nonetheless, we believe that it is possible to use different forms of parallelism to leverage massive memory bandwidth by scaling across a large number of devices to speed up MoE inference, making it comparable or faster than quality-equivalent dense models for extended inference scenarios and creating opportunities to make MoE based models cost efficient for inference in addition to training.

Conclusion and Release

We demonstrate that MoE based models can be applied to NLG task, reducing the training cost by 5x compared to dense, autoregressive transformer-based models like GPT-3 and MT-NLG 530B. Through MoE based low-cost training we hope to make high quality language models accessible to a broad audience, even with limited compute resources.

To this end we are releasing our end-to-end pipeline for training MoE based NLG models, along with specific example scripts and tutorial to help get started with our pipeline. We look forward to the application and the innovations that this may bring to the deep learning community.

Acknowledgement

This work was done in collaboration with Brandon Norick, Zhun Liu, Xia Song from the Turing Team, and Young Jin Kim, Alex Muzio, Hany Hassan Awadalla from Z-Code Team. We also thank Luis Vargas, Umesh Madan, Gopi Kumar, Andrey Proskurin and Mikhail Parakhin for their continuous support and guidance.